Home » BLOG » Business Development » Differentiation: Why does it matter?

Differentiation: Why does it matter?

Published in Managing Partner Magazine

The theme of this series of articles is the role that differentiation and positioning plays in the development of successful strategies within professional-service firms. Much of the series will concentrate on the importance of a clear framework in allowing coherent decisions to be made about the future direction of the business. These decisions will not just guide marketing and sales activity but will also influence recruitment policy, IT strategy, working practices and indeed the whole shape of the business going forward. If the strategy fails to do this, then it isn’t a strategy, it’s just window dressing.

Business development, defined in a holistic way, is concerned with the concept of brand as an all-embracing philosophy that initially defines and then actively manages the client experience of ‘what you get when you buy this firm’. This series will not consider differentiation as clever wallpaper- there is strong evidence to show that the sophisticated client sees through this very quickly – but rather as a form of surgery within a business. In short, to gain advantage that is sustainable, it is crucial to develop a differentiation strategy and competitive position that is credible, of value to clients, defendable from competitors and deliverable from the point of view of internal skills, competencies and resources.

Agreeing the decision framework is often the most difficult part of the process. Much of this difficulty arises as many firms find it difficult to get an objective assessment of their true competitive position. This will often require a firm to conduct a brutally frank self-assessment. The business needs to recognise and accept its strengths and inevitable weaknesses from both an internal perspective, and also that of its clients and those for whom it aspires to work in the future. If you can get this decision framework right, then the rest follows with relative ease; get it wrong, and the task is made immeasurably more difficult.

The reluctance to concentrate on certain types of work or specific market sectors may also be a barrier to progress. Where sophisticated clients are buying complex products and services, the philosophy of ‘nothing too big or too small’ or ‘we can do it all’ is not credible. The evidence is overwhelming that horses for courses is the name of the game – the question is what sort of horse are you (or do you think you could be) and what course will you run best?

Inevitably, this approach is heavily dependent on a philosophy of analysis and segmentation of clients and targets. This is because to be truly appealing, in a way that commands a price differential, will require a degree of focus. Choosing what to focus on and how to best position your services requires a clear understanding of client-market structures.

Overall, we will be looking at the importance of being determinant – being different in a way that is meaningful – and not just different.

What is strategy?

This is an interesting question and one that Michael Porter, one of the world’s leading management thinkers, posed in a Harvard Business Review paper in November 1996. What he went on to say raised a few eyebrows. It is instructive to pick up some of his themes wearing our professional-services hat.

At its most fundamental, strategy is about making choices and trade-offs. This should be self-evident but for many in the professions it is a difficult concept – we like to think (be it as individuals or organisations) that we can be all things to all men and that this is a virtue and strength. Of course, it is neither ñ what it often can be is an impediment to progress and a diluter of performance.

Many professionals talk about operational effectiveness in the guise of strategy. In an increasingly competitive marketplace, an efficient and well-structured operational model is clearly a driver of profitability. However, any managing partner can do the sums and see where the glass ceiling is. It is the point at which, even running their current business as efficiently as possible with good leverage and new business coming through the door as quickly as it can be turned around, a maximum level of sustainable profit is reached under their current business paradigm. What is now required is a strategic rather than operational shift. Ultimately, being an efficient operation is necessary but not sufficient.

“At its most fundamental, strategy is about

making choices and trade-offs. This should be

self-evident but, for many in the professions,

it is a difficult concept”

Most importantly, being very effective at doing the wrong thing will not save your business, although it might prolong the agony.

Strategy also means saying no to good ideas that don’t fit. This is tied to the first point and is often a difficult one for the line professional. But, one of the benefits of having a strategy is that it cuts through the debate that often surrounds good ideas that don’t fit with the overall strategy. For firms with a clear strategy, It’s easy: if it doesn’t benefit the strategy then we don’t do it. It might be a great idea and someone might make money from it, but it won’t be us.

Of course, in a professional context, it might also mean saying goodbye to good people who don’t fit with where you want to get to because of their skills, attitudinal approach or unwillingness to change. It’s important that this difficult subject is approached in a mature and objective way- we are not saying that the person is not skilled. Indeed, they may be highly regarded in their particular practice area and client profile, it is simply that their skills do not fit with the firm’s strategy. If the firm is serious about its strategy, such people will inevitably be marginalised over time as finite resources are invested elsewhere and other specialisms are prioritised over their own. Ultimately, they will make the decision to move on or simply grin and bear it for the last few years of their career. Both situations can lead to unnecessary animosity and it is surely better to deal with these directional issues up-front.

Finally, there is evidence emerging that successful strategy in the professions is about creating the best-possible fit between market opportunities and the organisation’s capabilities and competencies, or those to which it can stretch. Any differentiation strategy needs to be grounded in the reality of your business, people and clients, since this is your starting point. It also needs to be stretching in that it should seek to challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions about your firm and the way in which it wins work and retains clients. The strategy needs to pass the credibility test both internally and externally; at the same time, it must provide a convincing and compelling view of how things can be different and better.

What is differentiation?

As the topic of the series is differentiation and its role in strategy, it is useful to begin with a textbook definition of differentiation just to ensure that we are all thinking about the same thing. A differentiation strategy seeks to provide products or services unique or different to those of competitors in terms of dimensions widely valued by buyers.

This definition is presented, not as an academic or formulaic approach, but because it is often the case that the absence of a common understanding of what we are trying to achieve becomes the firm’s initial stumbling block. Too often within professional firms, there is an assumption from the senior-management team that concepts and vocabulary with which they are familiar have achieved widespread currency within their businesses through some magical process of osmosis. This is highly unlikely to be the case. The reticence of many professionals to admit perceived weakness by asking questions, together with an assumption that everyone but me knows this already, simply perpetuates this Chinese whispers approach to strategy and business development.

Let’s just drill a little deeper to look at the reasons why differentiation makes sense as a way of coping in a competitive environment for professional services. It could be argued that there are only three sustainable strategic positions for any business: be the lowest cost provider, differentiated or niche (which could be defined as a form of focused differentiation in a particular segment).

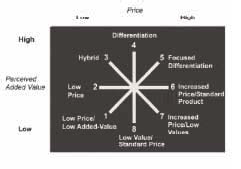

These three strategic orientations flow from the ‘strategy clock’ model (developed by Bowman), which proposed a total of eight positions based on two dimensions: price and perceived added value (see figure one). However, of these eight potential positions, three ultimately lead to failure, for example, the increased-price to low-value position, which fails to attract many customers outside monopoly situations. Of the five that are left, two are hybrids of the other three. For the purposes of this article, we will stay with the headline three: low-cost provider, differentiated and niche.

|

|

|

Figure one: Bowman’s strategy clock |

To be effective in each of these positions requires a business to make choices about the strategy that it will adopt in the market, the way that it will structure itself internally, how it will invest its resources and the risk profile of its on-going workload.

Making these choices in an active way is crucial. Many professional firms don’t and they end up stuck in the middle. Neither a niche player or differentiated, they are unable to present a value proposition to clients that separates them from the masses and are left to compete on the only dimension open to them: price.

The fundamental and economically key difference between the stuck-in-the-middle firm being forced into the low-cost-provider game and the business that has set out strategically to be a low-price operator is in their relative cost structures. Playing a low-price game without an aligned cost structure and business model is a fast track to disaster. Yet it is the battle that many firms find themselves fighting because they have not gained the necessary degree of control over the direction of their businesses.

|

|

|

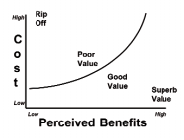

Figure two: The cost-benefits curve |

Another very simple model is the cost-benefits curve (see figure two). We can all appreciate that the price that someone is prepared to pay for a product or service (both monetary and non-monetary) is related to the benefits (both tangible and intangible) that they receive in return.

If costs are perceived to be high and benefits low, clients will have a huge sense of dissatisfaction. Of course at the other end of the scale, with benefits very high and costs very low, we find ourselves delivering superb, perhaps even unbelievable value. There will always be questions around the sustainability in the long term of such superb value positions.

Somewhere in the middle is a line of expectation around which most competitive battles are fought ñ the key being to deliver a set of benefits that are valued by a client, distinctive to your firm and at a price that makes acceptable returns for the business.

By unbundling this set of benefits, we start to see areas where competent performance is a necessity, but where we will gain no competitive advantage (marketers would call these hygiene factors) and those where we could choose to make differential investment to gain advantage.

With professional services, the word ‘perceived’ should be added to the benefits axis of this diagram, since many of the benefits that are delivered will have a perceived value in the mind of the client and will not be vested in any tangible product. Indeed, understanding how clients perceive the services that they receive and how the psychology underpinning perception can be managed is one of the most important tools that a professional firm can utilise in its differentiation strategy.

Putting all of this together, I offer my personal definition of what I believe every firm should be trying to achieve through its differentiation strategy in pragmatic, rather than academic, terms: you don’t have to be perfect, just discernibly better than your competitors at the things that matter most to your clients.

“You don’t have to be perfect, just discernibly

better than your competitors at the things that

matter most to your clients.”

It can be seen that this way of thinking also starts to pick up on a number of the core themes of strategy:

1. You can’t do it all. You need to choose the battles that you fight rather than letting them choose you;

2. You need to understand how clients think, what they value and how they choose. This understanding will allow you to build your business model around your clients’ values rather than your own perceptions;

3. You need to appreciate what the competition is doing. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage is the key output of a successful strategy. Differentiation is founded on understanding the competitive offerings.

Often professional services are not a discretionary purchase. The client has to buy from someone and they will seek out the best bundle of benefits (on their scale of importance not yours), and the best-balancing price. That will determine who will win the business.

These are the things that need to be understood. This is the knowledge and insight that you must gain and it is what effective differentiation is all about.

In the next article, I will look at the interplay between the firm, clients and competitors in more detail. I will outline some of the research into how benefits are perceived by clients when making purchase decisions and the importance of risk and trust.

You may also like

Search

Categories

Recent Posts

- Fighting fit

- The Challenges Of Leadership Are Different To The Challenges Of Management

- The Cultural Dimensions Of Leveraging Institutional Knowledge

- A knowledge-led approach to business development is key to law firm resilience

- Team Morale Is Directly Linked To The Ability To Deliver Differentiated Client Services