LAW FIRMS continue to grapple with a number of shifts in their competitive environment as difficult market conditions show little sign of abatement. These issues create a maelstrom that will tax the skills of any leadership team to the limit.

Here we consider some of the core drivers in this dynamic environment, offer insights to assist

firms in better understanding these issues, and provide some possible strategic options.

Leadership and management

Never before has the leadership of a law firm been so onerous or important. Giving a clear sense of direction, imbuing confidence and demonstrating resilience are the hallmarks of the leader. Add to this a need to both engender and facilitate change, and the challenge of leadership becomes clear.

Sitting alongside the requirements of the leader are those management tasks associated with

running increasingly complex firms operating in dynamic markets.

Looking to the future, it is clear that firms will need their most talented people to step forward for these roles. This creates a tension on two levels, which will require a structural response.

First, such people are often central to important client relationships; their enthusiasm to cede this role may well be limited. Second, the role of a full-time senior or managing partner necessarily means that one’s legal practice is put to one side. As a result there may be no role in the business at the conclusion of any significant tenure – departure from the firm may be almost inevitable.

Such a situation may be a deterrent to the most able candidates putting themselves forward for

such roles. How might firms respond?

It is interesting to note that the new incumbents at Freshfield Bruckhaus Deringer have publicly

stated that all partners in management positions will retain a significant level of client work

alongside their management positions, presumably leaving a return to practice more feasible at

the end of their tenure.

If such an approach becomes common practice, the implications of such actions on the

management structures of firms may be far reaching. The rise of COO and CEO positions appears inevitable to provide the management infrastructure that will be required. One can imagine an

approach akin to the relationship between the civil service and the government of the day evolving, in which policy and direction is provided by those elected by the partnership, with delivery being the responsibility of the permanent staff.

Strategy and direction

All firms lay claim to a strategy but, in truth, few have a compelling vision of a distinctive market position from which they can build sustainable competitive advantage. Fewer still possess the means by which to take their firms on this journey.

Repositioning is a compelling intellectual argument but difficult for any law firm to achieve in

practice, especially over a short timescale. Most will move in a series of small steps and will,

therefore, have to deal with the reality of their current market position over the next two years.

It is an unfortunate truth that for many, absolute strategic freedom will be limited and so immediate efforts should necessarily be focused on reducing the fixed cost base and attempting to build flexibility into the firm’s economic model by adopting alternative approaches to resourcing, some of which are discussed further.

Convergence around a limited number of strategic positions

In more challenging economic conditions, firms will converge around a limited number of strategic positions.

While there will be a small number of firms that deliberately adopt a lowestcost producer position, the vast majority will develop strategies based around differentiation of one form or the other.

At one extreme there will be highlyfocused niche players, offering a limited range of services to a limited and welldefined market. With the right strategy, such firms will gain a pricing advantage and build high-value brands; they also, of course, run the risk of putting all of their eggs in one basket should dramatic market changes affect their areas of focus.

Most firms will adopt a multidimensional differentiation model that identifies attractive segments of the market (by geography, sector, business type, service line or a combination) and build awareness and appeal to this defined group. This will be overlaid with a service proposition based on client intimacy – that is, we understand your specific needs and respond to them better than any other firm.

The stated strategy of most firms resides in one of these camps. The key is not in the stating of the strategy but in its delivery. We should expect to see much more rigour in the implementation of strategy going forward as economic conditions compel determined action.

Creating a global brand experience – Mergers but not as we have known them

Recent years have been marked by a number of transatlantic mergers, a trend likely to continue

as firms reposition. However, these are mergers in a different sense to those to which we have become accustomed. With the ‘Swiss Verein’ as the vehicle of choice, firms no longer share

profit pools but do commit to creating a global brand experience. DLA Piper, Hogan Lovells, SNR

Denton and Squire Sanders Hammonds are all adopters of this approach, with Baker & McKenzie

having long used the model.

Despite the accusation by some of not being real mergers, from a client perspective the reality

lies not in any profit-sharing agreement but rather, in the successful creation of a consistent brand and excellent client experience across a global footprint.

If this can be achieved within a Verein structure, a difficult historic barrier to merger activity (that is, markedly differing profit levels between firms) will have been removed. The amount of strategic freedom afforded to ambitious firms will increase and we should expect to see more mergers of this nature in the future.

Fixed fees – Routes to profit

While the hourly rate may not be extinct (and indeed, may always have a role for certain types of work in certain situations), there can be no doubt that moves towards fixed (or other alternative) fee arrangements are sweeping through the profession. There is a very significant transfer of risk in such arrangements – risk was carried predominantly by the client while now it resides primarily at the door of the firm.

To make money from fixed fees requires both an understanding of the costs of production and

high levels of control over them. It also, most certainly, will require firms to look at their operating model and to find cheaper ways of delivering the same results for their clients.

Concomitant with this will be continued efforts to streamline processes and ensure that work is

leveraged down to the lowest possible level. This is uncomfortable ground for the management

team and those lawyers who are now de facto part of knowledgeindustry production lines.

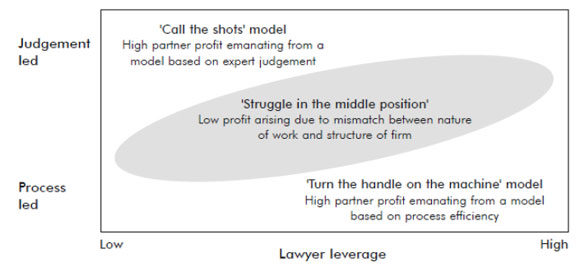

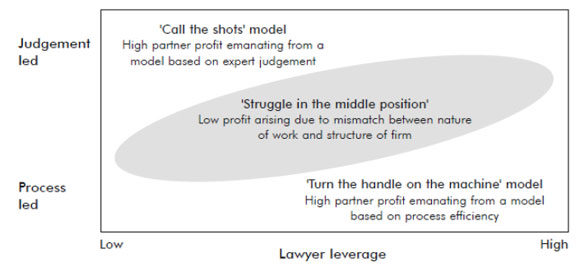

An alternative approach to the fixed-fee conundrum can be seen in a number of litigation-based

US firms. The model operates on low, rather than high, leverage and relies on expert partners

making judgments to bring matters to a successful conclusion without having the burden of very

significant overheads and the mouths of junior lawyers to feed.

Figure 1 shows these two different approaches and the challenging middle ground where

acceptable profits under a fixed price regime are increasingly difficult to achieve. We should expect leading-edge firms to make significant moves over the next year in remodelling their operations in one strategic direction or the other.

Flexible resourcing

A challenge for law firms structured along traditional lines lies in the inflexibility of its human resources. The culture of the profession emphasises the psychological contract between firm and employees; longevity sits at the core of this and an implicit understanding that the firm will view employees as a longer-term investment.

|

| Figure 1: Making money from fixed fees

|

This is still true for the core of the firm but the ebb and flow of work, at much keener prices than in the past, means that the resources needed to cope with peaks cannot be retained through troughs. A number of approaches are emerging to meet this need – for example, legal process outsourcing arrangements, sub-contracts with smaller firms, contract workers, flexible working arrangements and virtual networks. Each has its merits, will offer win-win cost advantages and may be appropriate in different circumstances.

They also create potentially significant challenges for those managing complex client services

and legal services. This is another area in which significant innovations and opportunities for

differentiation will emerge.

Change, change and more change

Responding to changing conditions by building a flexible and adaptive firm will be a key driver of success. The competency sine qua non that leaders should seek to hardwire into their firms is

the ability to change.

The firms that prosper will have levels of dynamism and flexibility that others simply cannot match. This will combine with strong leadership to provide clarity of purpose. Firms capable of adapting to the changing environment in ways that create competitive advantage will create a unique and compelling proposition.

We shall see such organisations emerging over the next two years and, inevitably, a number of

formerly great brands waning.